Athlete muscle recovery for ultra marathon running.

One man, a hundred kilometres, and one of the hardest endurance sports in the world.

Ultramarathons are marathons, only more so. A marathon is an athletic feat in its own right, but some ultramarathons almost defy belief. Tales of whole days spent running, through uneven and treacherous terrain, staving off the demons of exhaustion so strong that some runners start to hallucinate and vomit.

Ultramarathons can range from 50 kilometres, to the longest race in the world, the Self-Transcendence 3100 mile race. That’s almost five thousand kilometres! In this feat, runners will run 5649 laps of a 883 metre loop around a block in New York. That’s right, from six in the morning until twelve at night, they’re running. The race has a time limit of fifty two days, and has a strong volunteer base who help to feed, hydrate and look after runners.

New Zealand has its fair share of ultramarathons too. Events are held up and down the country, offering athletes a chance to push their limits and defy conventional wisdom. The longest and most famous race in New Zealand is the Tarawera Ultramarathon, offering conventional half and full marathon as well as a 52km, 100km and 160 kilometre race.

The average time for 100km races is about 10 to 15 hours, depending on your level of expertise. And it depends on the terrain too. Not every race is the same. You could be running a loop around a city block, through a bush trail, or up and over the hills. It depends on the race, and the cruelty of the organisers.

A hundred kilometre run almost defies belief. If it sounds daunting, that’s because that’s exactly what it is. It’s on the pinnacle of extreme endurance sports, and it takes a certain kind of person. The kind of person who could see ten hours of running in front of them and say “Why not?”

Foolhardy? Perhaps. Courageous? Maybe. Determined? Undoubtably.

Enter Christchurch ultramarathon runner, Simon Sigley.

If you saw Simon on the street, you wouldn’t assume that he was an extreme endurance athlete. He just looks like a regular, in-shape bloke. But that’s the thing - when it comes to ultramarathons, it’s what’s under the hood that matters. The mental fortitude, stamina to push through, ignoring your body creaking and crying out for mercy.

Simon just finished the hundred kilometre challenge around the Port Hills in Christchurch a few weeks ago. Moving through uncertain trails, trying to find the right path, he admits it was tough.

“It was brutal. Really brutal. But it was really fun. It was 100 kilometres all up. I finished just shy of 18 hours. I started at six in the morning, finished just before twelve at night.”

He says that the Port Hills Ultra was a test of not just his endurance, but his pathfinding ability as well.

“It was so hilly compared to other marathons, like with the elevation. Most of the other races I do they’re nice and fluffy and have all the signs to tell you to turn left, turn right. With this one there was a bit of orienteering involved. When you can’t see properly and don’t know where to go, you don’t wanna be looking at the phone.”

Teamwork is a large part of ultramarathons. Despite it being a race, there’s a camaraderie between racers. Maybe this is a recognition of the superhuman feat they’ve undertaken, where the real opponent is the course itself. Regardless, Simon got help from others, and says it’s a big part of ultramarathons.

Athlete muscle recovery for ultra marathon running.

One man, a hundred kilometres, and one of the hardest endurance sports in the world.

Ultramarathons are marathons, only more so. A marathon is an athletic feat in its own right, but some ultramarathons almost defy belief. Tales of whole days spent running, through uneven and treacherous terrain, staving off the demons of exhaustion so strong that some runners start to hallucinate and vomit.

Ultramarathons can range from 50 kilometres, to the longest race in the world, the Self-Transcendence 3100 mile race. That’s almost five thousand kilometres! In this feat, runners will run 5649 laps of a 883 metre loop around a block in New York. That’s right, from six in the morning until twelve at night, they’re running. The race has a time limit of fifty two days, and has a strong volunteer base who help to feed, hydrate and look after runners.

New Zealand has its fair share of ultramarathons too. Events are held up and down the country, offering athletes a chance to push their limits and defy conventional wisdom. The longest and most famous race in New Zealand is the Tarawera Ultramarathon, offering conventional half and full marathon as well as a 52km, 100km and 160 kilometre race.

The average time for 100km races is about 10 to 15 hours, depending on your level of expertise. And it depends on the terrain too. Not every race is the same. You could be running a loop around a city block, through a bush trail, or up and over the hills. It depends on the race, and the cruelty of the organisers.

A hundred kilometre run almost defies belief. If it sounds daunting, that’s because that’s exactly what it is. It’s on the pinnacle of extreme endurance sports, and it takes a certain kind of person. The kind of person who could see ten hours of running in front of them and say “Why not?”

Foolhardy? Perhaps. Courageous? Maybe. Determined? Undoubtably.

Enter Christchurch ultramarathon runner, Simon Sigley.

If you saw Simon on the street, you wouldn’t assume that he was an extreme endurance athlete. He just looks like a regular, in-shape bloke. But that’s the thing - when it comes to ultramarathons, it’s what’s under the hood that matters. The mental fortitude, stamina to push through, ignoring your body creaking and crying out for mercy.

Simon just finished the hundred kilometre challenge around the Port Hills in Christchurch a few weeks ago. Moving through uncertain trails, trying to find the right path, he admits it was tough.

“It was brutal. Really brutal. But it was really fun. It was 100 kilometres all up. I finished just shy of 18 hours. I started at six in the morning, finished just before twelve at night.”

He says that the Port Hills Ultra was a test of not just his endurance, but his pathfinding ability as well.

“It was so hilly compared to other marathons, like with the elevation. Most of the other races I do they’re nice and fluffy and have all the signs to tell you to turn left, turn right. With this one there was a bit of orienteering involved. When you can’t see properly and don’t know where to go, you don’t wanna be looking at the phone.”

Teamwork is a large part of ultramarathons. Despite it being a race, there’s a camaraderie between racers. Maybe this is a recognition of the superhuman feat they’ve undertaken, where the real opponent is the course itself. Regardless, Simon got help from others, and says it’s a big part of ultramarathons.

“I actually teed up with a guy who had it on his phone, I just ran with him so he could tell me where to go. I would’ve got lost for sure. That’s the thing, trail runners are extremely nice. We work together. You see it all the time, someone’s fallen down, you help others up. Even though it’s a race.”

The Port Hills race was Simon’s first 100km, but he dealt with it well.

“Thirty, forty, fifty (kilometres) was fine, because I’ve done that before. I’ve run for eleven hours, it’s only once you get past that you’re in the unknown. But even that was fine.”

He says running with someone else helped a lot in maintaining through the run.

“It’s good running with someone. You’re out in the dark, on the top of the Port Hills by yourself with your headlamp, that’s where the voices start you know? The demons are there, you know? (Laughs) But teaming up with a buddy, you can just talk smack the whole time. You alright? Yeah, you alright? Yeah, let’s keep going.

“The race director was bugging us because we were pulling into the aid stations, he goes oh, you’re in good spirits still and we just had to say sorry, you know? He wanted to see us broken, (laughs) but no.”

Simon wasn’t always a marathon runner. He wasn’t born with running shoes on. His first steps weren’t through a piece of tape at the end of a trail. In fact, his first exposure to the sport was being a supportive husband.

“My wife actually got me into it. I would partake, sit on the sideline, enjoying the weather and having a few beers.”

The couple were staying at a friend's place, and Simon’s wife took him for a run. He didn’t love it at the start.

“I did a house swap a few years back, and my wife was training heaps back then. She said she’d take me up the hills for a jog, up a summit road. It was a northwest day. I was nearly dead at the top, just puffing away.

“But she’d already signed me up for my first race. I was like no, no, but that’s where it began. Now I just keep going.”

Simon slowly ramped up. Twelve kilometres here, a half marathon there. But the distances grew alongside his enthusiasm for the sport. Simon was hooked, and just kept running. He says running has become a habit, regardless of how he feels afterwards.

“It’s funny. Every time you do a race and you get broken and hurt, and feel terrible, but you wake up in a couple days ntime and think right, what’s my next event? I made that one, I can go bigger. I think it’s an addiction thing, like you just want to go more and more and more.

“As an old man, there’s worse addictions, you know? (Laughs)”

“I actually teed up with a guy who had it on his phone, I just ran with him so he could tell me where to go. I would’ve got lost for sure. That’s the thing, trail runners are extremely nice. We work together. You see it all the time, someone’s fallen down, you help others up. Even though it’s a race.”

The Port Hills race was Simon’s first 100km, but he dealt with it well.

“Thirty, forty, fifty (kilometres) was fine, because I’ve done that before. I’ve run for eleven hours, it’s only once you get past that you’re in the unknown. But even that was fine.”

He says running with someone else helped a lot in maintaining through the run.

“It’s good running with someone. You’re out in the dark, on the top of the Port Hills by yourself with your headlamp, that’s where the voices start you know? The demons are there, you know? (Laughs) But teaming up with a buddy, you can just talk smack the whole time. You alright? Yeah, you alright? Yeah, let’s keep going.

“The race director was bugging us because we were pulling into the aid stations, he goes oh, you’re in good spirits still and we just had to say sorry, you know? He wanted to see us broken, (laughs) but no.”

Simon wasn’t always a marathon runner. He wasn’t born with running shoes on. His first steps weren’t through a piece of tape at the end of a trail. In fact, his first exposure to the sport was being a supportive husband.

“My wife actually got me into it. I would partake, sit on the sideline, enjoying the weather and having a few beers.”

The couple were staying at a friend's place, and Simon’s wife took him for a run. He didn’t love it at the start.

“I did a house swap a few years back, and my wife was training heaps back then. She said she’d take me up the hills for a jog, up a summit road. It was a northwest day. I was nearly dead at the top, just puffing away.

“But she’d already signed me up for my first race. I was like no, no, but that’s where it began. Now I just keep going.”

Simon slowly ramped up. Twelve kilometres here, a half marathon there. But the distances grew alongside his enthusiasm for the sport. Simon was hooked, and just kept running. He says running has become a habit, regardless of how he feels afterwards.

“It’s funny. Every time you do a race and you get broken and hurt, and feel terrible, but you wake up in a couple days ntime and think right, what’s my next event? I made that one, I can go bigger. I think it’s an addiction thing, like you just want to go more and more and more.

“As an old man, there’s worse addictions, you know? (Laughs)”

Simon has regular training to keep his body in shape. Running a hundred kilometres can leave you in major pain if you aren’t prepared. Horror stories from other races have people passing out, breaking bones in their feet, generally suffering through their race.

Simon, after having a few niggles in his body, sought the advice of a professional to find out how he can avoid falling to bits in a race.

“I’ve got a coach from Australia, Mark Green, a Kiwi trail legend, who made me a good program. When you’re on your learner plates and don’t know what you’re doing at the gym, it’s all about injury prevention.”

But what does that involve?

“It’s all running strength stuff. Kettlebell rotations, lunges, standing on one leg, it’s all on an app that I can just follow. Been doing it for a few years. My coach is huge on prevention.”

Simon says strength training is almost more important than the running, but it’s a chore.

“Runners are addicts. If I give you six runs and four strengths you’ll just find the time to do the runs but not the gym. But if you have to drop something, drop the run.”

Implementing strength training into your life can be a difficult adjustment, but is a major component in not developing dysfunctions or injuries. Try to head to the gym a couple times a week in conjunction with running, with a focus on developing core, hip and posterior chain strength. You can find a beginners guide to running and strength training here.

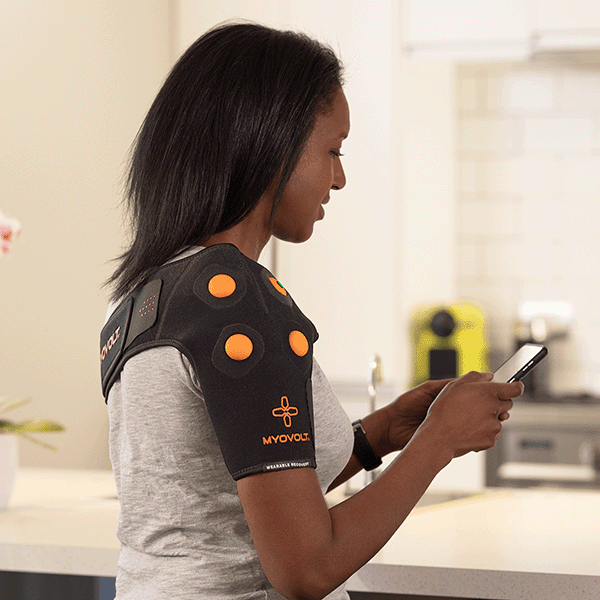

Simon also has something up his sleeve to help with warming up and recovery. He’s been using Myovolt for a couple of years now, and says it’s a great help.

“I have the leg units. Every time I do a long run and think I’m going to get DOMS (delayed on-set muscle soreness), so like a three to five hour run in the weekend, I’ll chuck two on the quads after the run, let it do a session, and then on the hamstrings.

“I think it helps, for sure. My niggles, little pains have been minimal. Putting Myovolt on has helped me. It's just been a good thing.”

Simon’s been improving his recovery and preparation game over the last while, and it’s paid off in spades.

“I honestly felt better finishing that 100 kilometre than I did after my first 20. And that’s remarkable, you know?”

Not to say there was no pain. Luckily, Simon has a specific trick for the day after a huge race.

“It’s always beer and pizza day. It’s actually written into my program, to do nothing but drink beer and eat pizza. After that, I take about a week off, and then slowly get back into running over about five weeks.”

Running a hundred kilometres is no small task. Simon has a simple trick to get started.

“My advice? Go for it. If I can go from zero to a hundred in a few years, anyone can.”

Myovolt. Good vibrations. Great recovery.

Featured in this story

Myovolt Leg fits comfortably around the left or right knee, quad, hamstring or calf and delivers a 10 minute focal vibration treatment at the press of a switch. The neoprene leg brace has an adjustable fit ...

Simon has regular training to keep his body in shape. Running a hundred kilometres can leave you in major pain if you aren’t prepared. Horror stories from other races have people passing out, breaking bones in their feet, generally suffering through their race.

Simon, after having a few niggles in his body, sought the advice of a professional to find out how he can avoid falling to bits in a race.

“I’ve got a coach from Australia, Mark Green, a Kiwi trail legend, who made me a good program. When you’re on your learner plates and don’t know what you’re doing at the gym, it’s all about injury prevention.”

But what does that involve?

“It’s all running strength stuff. Kettlebell rotations, lunges, standing on one leg, it’s all on an app that I can just follow. Been doing it for a few years. My coach is huge on prevention.”

Simon says strength training is almost more important than the running, but it’s a chore.

“Runners are addicts. If I give you six runs and four strengths you’ll just find the time to do the runs but not the gym. But if you have to drop something, drop the run.”

Implementing strength training into your life can be a difficult adjustment, but is a major component in not developing dysfunctions or injuries. Try to head to the gym a couple times a week in conjunction with running, with a focus on developing core, hip and posterior chain strength. You can find a beginners guide to running and strength training here.

Simon also has something up his sleeve to help with warming up and recovery. He’s been using Myovolt for a couple of years now, and says it’s a great help.

“I have the leg units. Every time I do a long run and think I’m going to get DOMS (delayed on-set muscle soreness), so like a three to five hour run in the weekend, I’ll chuck two on the quads after the run, let it do a session, and then on the hamstrings.

“I think it helps, for sure. My niggles, little pains have been minimal. Putting Myovolt on has helped me. It's just been a good thing.”

Simon’s been improving his recovery and preparation game over the last while, and it’s paid off in spades.

“I honestly felt better finishing that 100 kilometre than I did after my first 20. And that’s remarkable, you know?”

Not to say there was no pain. Luckily, Simon has a specific trick for the day after a huge race.

“It’s always beer and pizza day. It’s actually written into my program, to do nothing but drink beer and eat pizza. After that, I take about a week off, and then slowly get back into running over about five weeks.”

Running a hundred kilometres is no small task. Simon has a simple trick to get started.

“My advice? Go for it. If I can go from zero to a hundred in a few years, anyone can.”

Myovolt. Good vibrations. Great recovery.

Featured in story

Myovolt Leg fits comfortably around the left or right knee, quad, hamstring or calf and delivers a 10 minute focal vibration treatment at the press of a switch ...